There are many hypotheses about the construction of Stonehenge, but we keep asking ourselves the same question: how on earth did they build such a monument in ancient times? More than a few archaeologists have been committed to searching for the necessary clues much further back in time, and now a new study seems to shed light on the engineers’ understanding of the past. The clue was in Spain. In an amazing stone monument built 1,000 years earlier.

The Menga dolmen. Located in Antequera, Spain, we are in front of one of the most important most impressive megalithic monuments and oldest in Europe, one dating from around 3,500 B.C. Its importance lies in its sheer size, with a chamber believed to be a 25-meter burial chamber built of huge stones weighing tons, and its unusual orientation towards the Peña de los Enamorados, a distinctive feature among dolmens, which are often aligned with solar events.

However, this one is unique, a masterpiece of prehistoric architecture. Let’s think for a moment that its combined weight is approximately 1,140 tons, heavier than two Boeing 747 aircraft loaded with passengers. Therein lies part of the mystery and magic of this kind of construction, and a new study provides clues about the knowledge that was available to build similar works.

The new study. Published a few days ago in the journal Science Advancesthe analysis by a team of archaeologists has revealed that it was built with an extraordinary level of scientific understanding. “I have always been amazed at the engineering skills required to build this dolmen.” account Michael Parker Pearsonan archaeologist at University College London. “The work reveals how precisely it must have been done, with an extraordinary eye for dimensions and angles. With such large stones, they could not have afforded to make mistakes in maneuvering them into position.”

For José Antonio Lozano Rodríguezgeologist of the Spanish Institute of Oceanography and first author of the research, “entering inside and contemplating such a colossal Neolithic monument awakened my curiosity to know more about this dolmen. What struck me most about the Menga dolmen was its monumentality”.

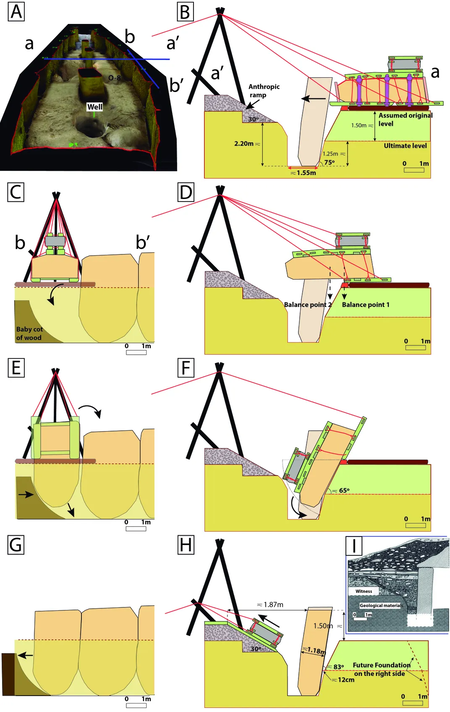

Recreation of the proposed process of placing the standing stones.

How to move tons of stone. Apparently, what the researchers did was to dive into what is known as the geoarchaeological analysis of the site, examining laser and visual scans of previous excavations, and ethnographic descriptions of the construction techniques and topography of the area.

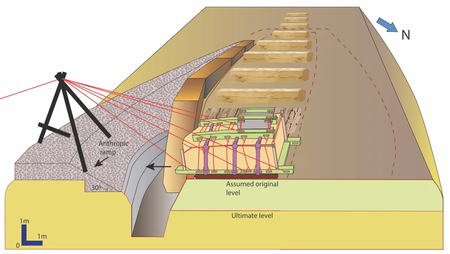

Once the data were collected, the team deduced something unknown: the construction process of Neolithic engineers. They started from known facts. For example, a previous study had already established that the stones came from a quarry located one kilometer away, at a height strategically higher than that of the Menga dolmen. How? It is thought that the builders transported the stones using sledges on a track made with wooden beams, which implies a knowledge of friction, acceleration and center of masses.

Recreation of the proposed placement process of the standing stones inside the dolmen.

Carving the stones, key. As detailed, once on site, the stones that formed the walls and the columns were placed in a vertical position in deep cavitiesso that as much as a third of each stone was left underground. The builders, they suggest, probably accomplished this by using counterweights and ramps that must have taken into account the relatively soft (and therefore easily damaged) nature of the sandstone rock.

As for the stones in the wall, the study’s proposal is that they were carved so that they interlocked and leaned against each other, thus increasing the stability of the structure. “These people had no plans to work with nor, as far as we know, previous experience in building something like this.” explains study co-author Leonardo García Sanjuán.an archaeologist at the University of Seville. “There’s no way you can do that without at least a basic understanding of the science.”

The principle of the arc, for the first time. The researchers’ work emphasizes that the walls slope slightly inward, forming angles of between 84/85 degrees, so that the upper part of the chamber is narrower than the trapezoidal-shaped lower part. In this regard, the largest of the five capstones was carved to increase stress distribution, creating a rudimentary arch, with its center higher than its sides.

This is far from trivial. According to the studyAccording to the study, “to our knowledge, this is the first time that the arch principle has been documented in human history”. Setting up the chamber with its walls partially underground also meant that the capstones could be placed on top without having to lift them very high. They then excavated the ground inside to lower the chamber’s floor level, while the outside was covered with earth to further insulate and stabilize the construction.

Conclusion. The findings represent a before and after about what was thought of the knowledge of architecture in the Neolithic. The study helps to understand, not only the execution of the Menga dolmen, but also the works and monuments that came later, such as Stonehenge itself or the step pyramid of Zoser.

For this reason, the team of experts has no other word to define the handling that was had of all these concepts. “We have to call it science. We’ve never talked about Neolithic science before, just because maybe we were too arrogant to think that these people could do it the way we do it.”

In fact, as García Sanjuán assures CNNIf any engineer today would try to build Menga with the resources that existed 6,000 years ago, I don’t think he would be able to do it,” he says.

Image | PexelsLeonardo García Sanjuán, José Antonio Lozano Rodríguez et al, Science Advances

In Xataka | We have been obsessing for years about the meaning of Stonehenge. Its great enigma was another: how its six-ton altar traveled 700 km.

In Xataka | The acoustics of Stonehenge has surprised the experts: an open space with acoustics like that of a cathedral